Category: Financial Literacy

-

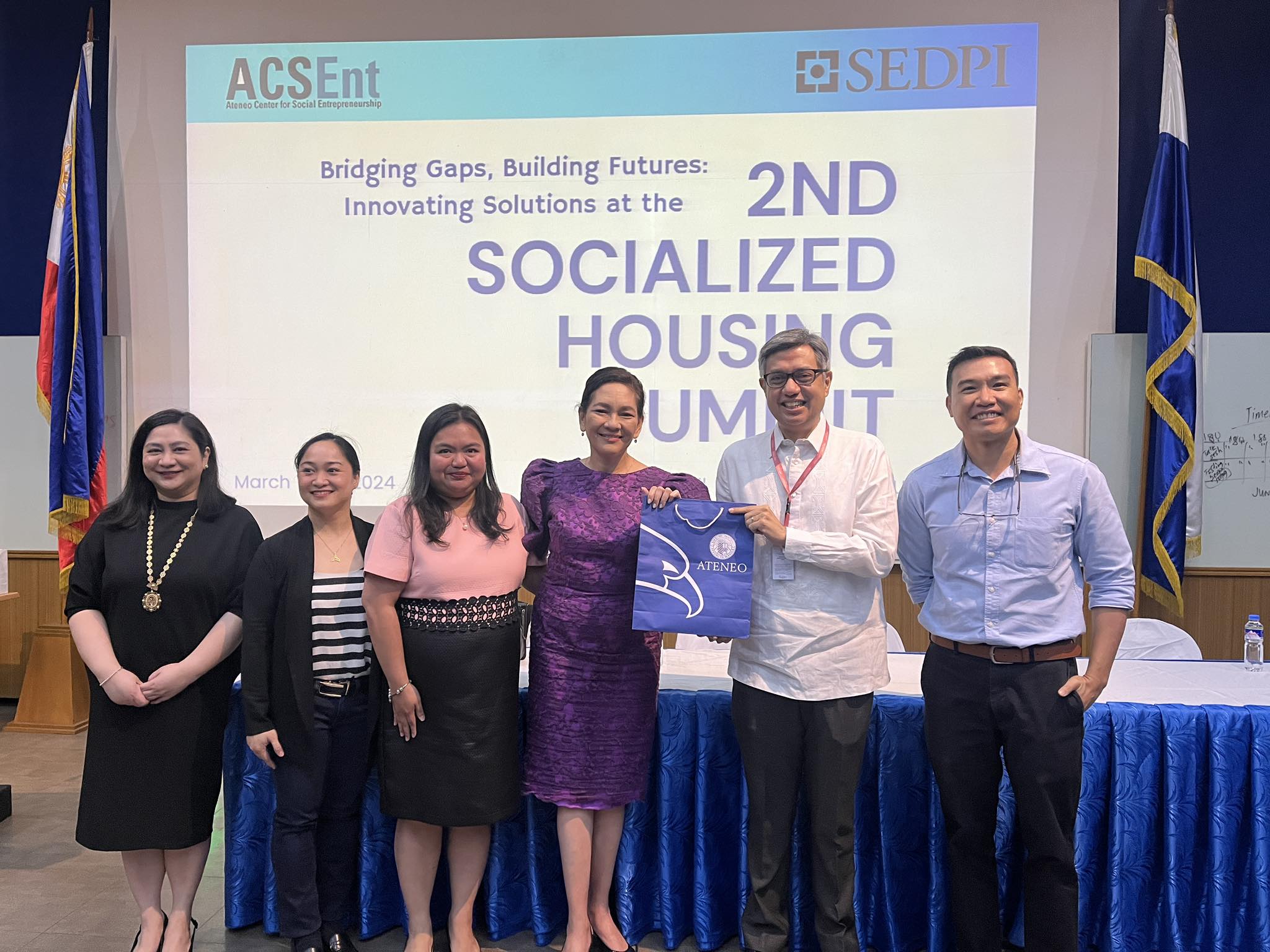

DENR’s Engr. Romeo P. Verzosa Outlines Land Titling Reform at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

The second day of the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, co-organized by the Ateneo Center for Social Entrepreneurship (ACSent) and Social Enterprise Development Partnerships Inc. (SEDPI) on March 18-19, 2024, at Ateneo de Manila University, featured Engr. Romeo P. Verzosa, Assistant Director of the DENR – Land Management Bureau. His presentation provided an essential overview of…

-

SHFC Aims to Transform Lives with Resilient Communities Amid Housing Challenges

At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit held at Ateneo de Manila University, Atty. Junefe G. Payot from the Social Housing Finance Corporation (SHFC) presented an approach to combat the Philippines’ housing backlog through resilient community-driven projects. Amidst a critical period where the production of socialized housing units plummeted to an all-time low in 2023, SHFC’s…

-

Senator Risa Hontiveros Advocates for Innovative Social Housing Solutions at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

Manila, Philippines – At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit held at Ateneo de Manila University, Senator Risa Hontiveros delivered a compelling speech, outlining the dire need for innovative and inclusive solutions to the Philippines’ housing crisis. Addressing a gathering of developers, microfinance institutions, academes and housing advocates, Senator Hontiveros emphasized the dream of every Filipino…

-

Empowering the Marginalized: SEDPI’s Innovative Path in Nanoenterprise Development

Empowering the Marginalized: SEDPI’s Innovative Path in Nanoenterprise DevelopmentVince RapisuraJanuary 11, 2024 Established in 2004, the SEDPI Group of Social Enterprises focuses on empowering marginalized Filipino communities via sustainable nanoenterprise growth. Their multifaceted approach includes nanofinancing, social investments, and financial education, addressing poverty and promoting financial stability. Despite advances in microfinance, poverty and high indebtedness…

-

SEDPI and Land Bank of the Philippines: Strengthening Ties for Sustainable Development

Rosario, Agusan del Sur – In a significant step towards enhancing their long-standing partnership, SEDPI hosted a comprehensive field visit for representatives from the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) at their KaNegosyo Bayugan branch. This visit, involving key personnel from both organizations, served as a platform for collaborative discussion and strategic planning. The day…

-

The Rice Price Cap in the Philippines: Pros, Cons, and Long-Term Implications

In the wake of soaring rice prices, the Philippines has found itself in the midst of a contentious debate over the imposition of a rice price ceiling. As the staple food of the nation, rice plays an integral role in the daily lives of millions, making its affordability and accessibility crucial. President Bongbong Marcos, wearing…

-

Regulatory landscape of microfinance in the Philippines: An overview

Microfinance has emerged as a critical tool for poverty alleviation and financial inclusion in the Philippines. The government has recognized its potential and has enacted several laws and regulations to promote and regulate the sector (Llanto & Fukui, 2015). This paper examines the key regulations governing microfinance in the Philippines and their implications for the…

-

Power to the Nano: How SEDPI is shaking up economic norms for the better

The SEDPI Group of Social Enterprises is a Philippines-based organization that operates with the aim of alleviating poverty among Filipinos worldwide. Since its inception in 2004, it has grown to include eight collaborative organizations executing three key programs: SEDPI KaSosyo, SEDPI KaNegosyo, and Usapang Pera. These programs focus on social investments, nanofinancing, and financial education…

-

SEDPI and PhilHealth partnership: An empowering step towards accessible health insurance for nanoenterprises

The significance of the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) under the Universal Health Care (UHC) Act in the Philippines is undisputable. As a nation, we must ensure that healthcare is both accessible and affordable to every Filipino citizen, particularly those from marginalized sectors. SEDPI, an organization that champions social investments, nanofinancing, and financial education to alleviate…

-

SEDPI at 19: Pioneering change and empowering communities

Warm greetings to you all. It fills me with immense joy and gratitude to stand before you on this significant occasion – the 19th anniversary of the SEDPI Group and the inauguration of our new headquarters in Rosario, Agusan del Sur. It’s wonderful to see so many familiar faces and new ones alike, as we come…