SEDPI is a group of social enterprises that provide capacity building and social investments to development organizations and directly to microenterprises. We serve ~8,000 microenterprises in Agusan del Sur and Surigao del Sur, two of the poorest provinces in the Philippines.

Most of our members, about nine in 10, are women with an average age of 42. These women are typically into vending, farming, fishing, dress making, selling food, and livestock backyard raising.

Community assessments

Every week, since the community quarantine was imposed on March 15, 2020; SEDPI conducted community assessment research with its members. These were conducted on March 15, March 30, April 5 and April 14; through rapid survey via text messaging and calls with our members.

The rapid community assessment aims to determine the economic impact of COVID-19 on our members and to have a clearer picture of what transpires on the ground. We asked our members the following:

- Status of their livelihood – unaffected, weakened or stopped

- Experience symptoms of COVID-19

- Access to government assistance

- Support needed after the community quarantine

Impact of COVID-19 to microenterprises and informal sector

All microenterprises were negatively affected due to COVID-19. Immediately after the community quarantines were announced, 34% of microenterprises stopped their livelihood. After two weeks this spiked to 51% and slightly recovered to 41% after a month of lockdown.

Some microenterprises reopened their livelihood because they need to earn income to have enough budget to buy rice at the minimum. They sourced locally-available inputs to do this and were able to sell banana cue, camote cue, cassava cake and rice cakes among others.

Majority of microenterprises or 59% reported that their livelihood weakened. Of which, 59% and 31% reported significant and severe weakening of livelihoods resepectively.

Supply chain disruption; inability to deliver goods and services; and prohibition to open non-essential businesses were the main reasons given for stopping or weakning of their livelihoods. With families having to stay home and most business remain closed, there are very few buyers of their products and services. Most barangays prohibit entry of non-residents which prevent others from going to work.

Exposure to COVID-19

An encouraging finding in the rapid community assessment is that only 2 of the 6,071 respondents are persons under monitoring. This may be a positive sign that the community quarantine is effective in containing the rapid spread of the virus.

The quarantine period was extended to April 30 and the question now is how much longer can the poor endure its negative effects to their livelihoods. Many of them are saying that they might die first of hunger before getting infected with COVID-19.

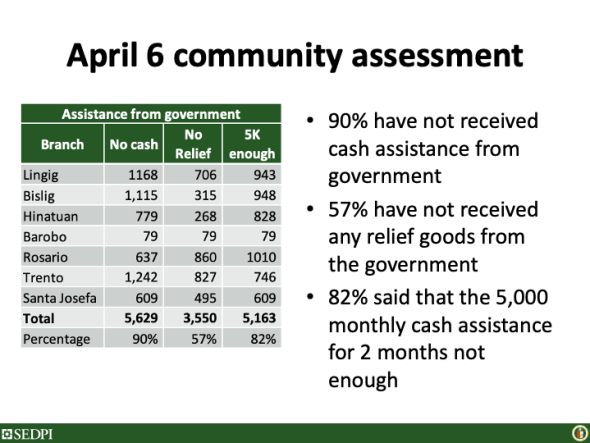

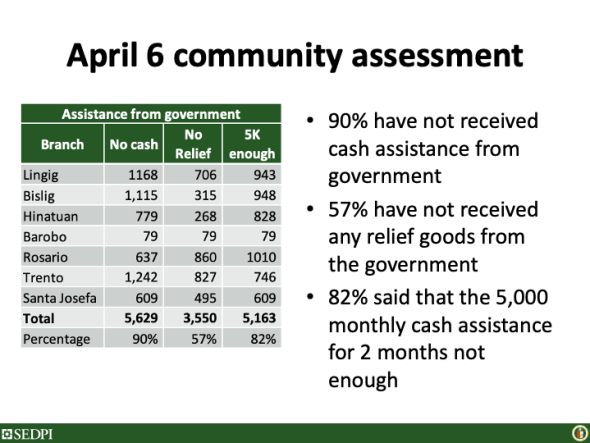

Access to government assistance

It is important to consider the well-being of low-income groups and provide them with enough economic support and social safety nets during this quarantine period. The government’s cash assistance and emergency relief is very much needed on the ground to help them survive.

Only one of ten microenterprises or 11% were able to receive cash assistance; and 60% received relief goods from the government as of April 14. This is an improvement of 1% and 17% respectively from the previous week showing marginal improvement in access to government assistance.

Those who received cash assistance got PhP3,000 to PhP4,000. Most of them received PhP3,600 cash assistance through the 4Ps program of the Department of Social Welfare and Development.

Relief goods received were composed of rice, canned goods and soap. Most of those who received these said that the supply will only last them for 1-2 days. Most of the respondents or 82% also expressed that the PhP5,000 cash assistance will not be enough to cover their daily needs in the next two months.

Recommendations during community quarantine

Hasten government cash assistance and relief

The government needs to hasten release of cash assistance and relief goods to microenterprises and the informal sector. These will alleviate their burden and enable them to survive the community quarantine.

Prohibit interest accrual on MSEs loans

Interest accrual for loan of micro and small enterprises during the quarantine period should be prohibited. On April 3, Ateneo-SEDPI Microfinance Capacity Building program released a position paper regarding this.

The continued charging of interest during community quarantine is socially unjust since this gives additional burden to microenterprise and small enterprises at a time when they can barely survive. This is an unnecessary additional expenses that will make their lives even harder during the rebuilding and recovery phase.

Mass testing

Prioritize mass testing to suspect and probable COVID-19 individuals who belong to low income groups, especially in urban centers, where spaces are cramped and transmission could happen faster.

Free testing services should be provided to make sure that transmission in low-income groups is prevented and managed properly. Local government units should have isolation areas for PUIs and PUMs to prevent the spread of the disease in rural and urban poor communities.

Recommendations immediately after community quarantine

The rapid community assessment showed that 77% of respondents request for cash assistance to restart their livelihood after the community quarantine. Many of the members or 35% would still need relief goods, especially food, immediately after the quarantine and A few or 12% need work to have source of income.

The rapid community assessment showed that 77% of respondents request for cash assistance to restart their livelihood after the community quarantine. Many of the members or 35% would still need relief goods, especially food, immediately after the quarantine and A few or 12% need work to have source of income.

Cash assistance to restart livelihoods through MFIs

Request for cash assistance to restart livelihoods should be coursed through microfinance institutions (MFIs) to eliminate dole-out mentality. The cash assistance should be given, at the minimum, as 0% loans to microenterprises and the informal sector.

MFIs are well positioned to provide this intervention since they would need to support the rebooting of the livelihoods of their client base. The cash assistance will be collected alongside restructuring of existing loans of clients so that financial service delivery will continue.

Bail out MFIs

MFIs access funds from commercial banks and government financial institutions that they extend as microcredit to low income groups. Based on the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor’s (CGAP) estimate, an 85% repayment rate in MFIs would only have sufficient cshflow to last in the ext six months.

The impact of the pandemic will surely negatively impact repayment rates of MFIs. Based on the figures of those negatively affected, SEDPI estimates that it repayment rates in the next three months after the quarantine period may hit as low as 20% to 30%. Due to this, most MFIs will experience liquidity problems.

Government should intervene and infuse capital in the form of equity to MFIs to fund the proposed cash assistance intended to restart microenterprise livelihoods. Another way of doing this is to temporarily convert debt obligations of MFIs from commercial banks and especially from government financial institutions to equity to ease pressure in debt repayments.

MFIs will eventually pay this equity back to the government, perhaps event at a premium, once they recover from the crisis. SEDPI strongly suggests moving away from debt-based development assistance since interest will ultimately be passed on as additional burden to microenterprises and the informal sector.

This strategy is similar to the bailout of governments to large financial institutions during the 2008 financial crisis. If governments are willing to bail out large corporations, they should also be willing to do the same to MFIs that directly help those at the bottom of the pyramid.

Pay for work programs

Development organizations and government should provide pay-for-work programs to spur local economic development. This will create temporary employment and give purchasing power that will augment efforts to restart of livelihoods.

0% SSS and Pag-IBIG calamity loans

Microenterprises and informal sector who are members of SSS and Pag-IBIG could benefit from the calamity loans offered. Per published policy of these two organizations, members are allowed to borrow calamity loans against their personal contributions.

The interest rate for calamity loan is 5.95% for Pag-IBIG and 10% for SSS. It is highly recommended to bring the interest on the calamity loans to 0%, since these are drawn from personal contributions of members anyway.

Recommendations for the long term

Ease in access to identity documents

Access to government basic services starts with identity. The Philippine Statistics Authority should streamline processes for low-income groups to get government identification documents such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, and licenses.

Greater financial inclusion

It is also important to focus more on financial inclusion to make sure that bank accounts are opened for all low-income families so that they can easily access cash transfers and cash relief in times of disaster. This will ensure that funds truly land in the pockets of low-income groups, and could potentially reduce corruption and patronage politics.

Universal disaster insurance

It is also high time to have universal disaster insurance since the Philippines ranks high in the World Risk Index. This will make us better prepared for disasters and pandemics in the future.

The scheme will provide funds to affected communities, especially low income groups, to cope with the disaster and to rebuild livelihoods. Having disaster insurance will eliminate the need for low income groups to beg for government assistance from politicians.

Tap vast network of MFIs

Microfinance institutions are rooted well in communities and have vast networks that penetrate even the most remote areas. This makes them suitable for information dissemination as well as for distribution of government assistance.

Prioritize support and assistance to the bottom of the pyramid

We may be already enjoying the positive effect of the commuity quarantine to prevent the sudden spread of COVID-19. However, its negative economic impact especially to vulnerable sectors such as microenterprises and the informal sector, is undeniable.

To sustain and complement the gains of the quarantine, priority and free mass testing to low income groups is needed. This will hopefully flatten and at the same time shorten the curve.

Government should hasten delivery of cash and relief assistance to low income groups to alleviate the burden of low income groups. MFIs could complement barangay level legwork for information dissemination and distribution of government assistance with its vast network and penetration in rural areas.

To ease the economic burden of low income groups, the government should stay true to the intent and spirit of the Bayanihan Act, that prohibit accrual of interest and other fees during the quarantine period.

Immediately after the quarantine period, to help jumpstart the economy, the government could provide pay for work programs; and provide cash assistance to microenterprises through MFIs. It could bailout MFIs to ensure continued delivery of much needed microfinance services to the poor.

The proposed 0% calamity loans of Pag-IBIG and SSS could provide much needed relief to microenterprises and the informal sector. In the longer term, structural challenges could be addressed through providing ease in access to identity documents, broader financial inclusion, and universal disaster insurance.

When we channel resources to help microenterprises and the informal sector, we make our nation better poised to recover faster from the negative effects of COVID-19.

SEDPI offers the Social Welfare Protection Program (SWePP), where members can avail microinsurance coverage for their families in the Philippines or themselves. SWePP is a consolidated microinsurance and social safety net program and provides security and protection to low-income SEDPI members.

SEDPI offers the Social Welfare Protection Program (SWePP), where members can avail microinsurance coverage for their families in the Philippines or themselves. SWePP is a consolidated microinsurance and social safety net program and provides security and protection to low-income SEDPI members.

Insurance is not an investment. You are not after financial gain. It is for protection against financial losses and involves exchanging the uncertain prospect of large losses for the certainty of small, regular premium products.

Insurance is not an investment. You are not after financial gain. It is for protection against financial losses and involves exchanging the uncertain prospect of large losses for the certainty of small, regular premium products.

His daughter, Rica Caneta, is a private school teacher. She has been helping him sell some of his works, “I made a hanging cabinet and a storage cabinet with the extra wood from the previously commissioned projects. I sold them for P2,500 and P3,000 respectively. Rica is working from home so she takes some time to promote my pieces through social media.”

His daughter, Rica Caneta, is a private school teacher. She has been helping him sell some of his works, “I made a hanging cabinet and a storage cabinet with the extra wood from the previously commissioned projects. I sold them for P2,500 and P3,000 respectively. Rica is working from home so she takes some time to promote my pieces through social media.”  Federic’s son, Drake, is an animal handler and is supporting the family through these times, “My children are providing financial support we need. Our monthly expenses are usually P10,000 which was primarily covered through my business.” He has discovered the potential of taking his business online to help it grow, “I would need around P10,000 to buy materials for future orders. Online sales have made me realize that professional guidance in promoting our business would really help it expand.”

Federic’s son, Drake, is an animal handler and is supporting the family through these times, “My children are providing financial support we need. Our monthly expenses are usually P10,000 which was primarily covered through my business.” He has discovered the potential of taking his business online to help it grow, “I would need around P10,000 to buy materials for future orders. Online sales have made me realize that professional guidance in promoting our business would really help it expand.” However, these sales do not provide stability for the pisonet.

However, these sales do not provide stability for the pisonet.  JJS Suds is a connection to the local community, “We would normally have 30 to 50 customers a day before the lockdown. We are lucky if there are five customers these days. Our daily revenue would reach up to P15,000 per day and that target is now P5,000.” John has had to cut corners to adapt to the new normal, “We had seven workers on a daily basis and now there are only two at any given time. The store is only open for limited hours because customers no longer come in late at night. It has led to slower service delivery. We have also started using electric fans.”

JJS Suds is a connection to the local community, “We would normally have 30 to 50 customers a day before the lockdown. We are lucky if there are five customers these days. Our daily revenue would reach up to P15,000 per day and that target is now P5,000.” John has had to cut corners to adapt to the new normal, “We had seven workers on a daily basis and now there are only two at any given time. The store is only open for limited hours because customers no longer come in late at night. It has led to slower service delivery. We have also started using electric fans.” Communication is a constant with John’s regular clientele. The staff coordinate with customers on Facebook. John has also decided to bring the business to his regulars, “We also support our personnel needs by helping with the laundry and delivery. The shop currently relies on delivery modality to remain operational. Finding alternative solutions is necessary to keep the business running.”

Communication is a constant with John’s regular clientele. The staff coordinate with customers on Facebook. John has also decided to bring the business to his regulars, “We also support our personnel needs by helping with the laundry and delivery. The shop currently relies on delivery modality to remain operational. Finding alternative solutions is necessary to keep the business running.” Pureza’s shop is her saving grace during the uncertainty, “We need P9,000 for our household expenses and about P7,000 for the store.” The store is a constant for her. Its history in the community mirrors Pureza’s presence and determination, “We reinvest all of our profits into the shop. I’m obtaining inventory through other channels because I want to see my store grow despite the circumstances.”

Pureza’s shop is her saving grace during the uncertainty, “We need P9,000 for our household expenses and about P7,000 for the store.” The store is a constant for her. Its history in the community mirrors Pureza’s presence and determination, “We reinvest all of our profits into the shop. I’m obtaining inventory through other channels because I want to see my store grow despite the circumstances.”

The city was distributing P2,000 for tricycle drivers which Jhun was unable to collect, “I believe it is because my house is far from the collection point. The local government did provide us with rice and sardines on two occasions. We have also received grocery items from

The city was distributing P2,000 for tricycle drivers which Jhun was unable to collect, “I believe it is because my house is far from the collection point. The local government did provide us with rice and sardines on two occasions. We have also received grocery items from  Inflation of necessary supplies during a disaster event makes business continuity an even greater challenge. Edwin’s main concern is procuring inventory, “We pick up essential ingredients from outside the local area because of lack of availability. The city’s clustering policy during the lockdown prevents vendors from sourcing some of the vegetables we need from Bukidnon.” The scarcity in supply and increase in price has forced Edwin to shut down despite being able to operate under COVID-19 safety guidelines. “The price of vegetables has inflated by 20 to 30%. Rice and grains have only gone up 10%. However, these cumulative prices make it impractical to continue operations.” The emerging caterer hopes that small businesses will receive the aid they need to carry on after the restriction, “We would appreciate logistical support, availability of supplies from the National Capital Region and other key cities, tax relief, and easing of local cluster market restrictions.”

Inflation of necessary supplies during a disaster event makes business continuity an even greater challenge. Edwin’s main concern is procuring inventory, “We pick up essential ingredients from outside the local area because of lack of availability. The city’s clustering policy during the lockdown prevents vendors from sourcing some of the vegetables we need from Bukidnon.” The scarcity in supply and increase in price has forced Edwin to shut down despite being able to operate under COVID-19 safety guidelines. “The price of vegetables has inflated by 20 to 30%. Rice and grains have only gone up 10%. However, these cumulative prices make it impractical to continue operations.” The emerging caterer hopes that small businesses will receive the aid they need to carry on after the restriction, “We would appreciate logistical support, availability of supplies from the National Capital Region and other key cities, tax relief, and easing of local cluster market restrictions.” Keeping their office is the biggest challenge, “Our maintenance cost fluctuates between P5,000 to P10,000 and the rental fee for the office is P7,000. We have used our savings to continue paying the rent and any vehicle maintenance that was necessary.” Shirly also has to consider the family expenses, “My sister works in Hong Kong and has sent us remittance of P20,000 during the lockdown. We were able to use the money for four months of household expenses. If we can resume operations soon, we would only need P5,000 to start functioning again.”

Keeping their office is the biggest challenge, “Our maintenance cost fluctuates between P5,000 to P10,000 and the rental fee for the office is P7,000. We have used our savings to continue paying the rent and any vehicle maintenance that was necessary.” Shirly also has to consider the family expenses, “My sister works in Hong Kong and has sent us remittance of P20,000 during the lockdown. We were able to use the money for four months of household expenses. If we can resume operations soon, we would only need P5,000 to start functioning again.” Multiple income-generating opportunities are a proven solution for many small businesses to sustain their needs. The COVID-19 restrictions have limited these prospects to entrepreneurs. Giselle currently works as a cashier for a university. It is the only stable income for the household. The lack of earnings has forced her to take loans, “My husband has a van that he would use for delivery operations. He would regularly work for Lazada but that has also stopped since March.” Loss of revenue sources has multifold consequences for microentrepreneurs. “We have lost around P19,000 a month since the lockdown. We also had an SUV that we would rent out through the Grab app. Unfortunately, we had to give it back to the dealership because we were unable to cover the monthly payment or the driver’s salary.”

Multiple income-generating opportunities are a proven solution for many small businesses to sustain their needs. The COVID-19 restrictions have limited these prospects to entrepreneurs. Giselle currently works as a cashier for a university. It is the only stable income for the household. The lack of earnings has forced her to take loans, “My husband has a van that he would use for delivery operations. He would regularly work for Lazada but that has also stopped since March.” Loss of revenue sources has multifold consequences for microentrepreneurs. “We have lost around P19,000 a month since the lockdown. We also had an SUV that we would rent out through the Grab app. Unfortunately, we had to give it back to the dealership because we were unable to cover the monthly payment or the driver’s salary.”

Agrarian Reform Beneficiary Organizations (ARBO) in Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, Maguindanao, and Lanao del Sur Provinces remain covid free. This is the result of the ARBO covid-19 quick assessment conducted by SEDPI on April 20-24, 2020.

Agrarian Reform Beneficiary Organizations (ARBO) in Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, Maguindanao, and Lanao del Sur Provinces remain covid free. This is the result of the ARBO covid-19 quick assessment conducted by SEDPI on April 20-24, 2020.

The rapid community assessment showed that 77% of respondents request for cash assistance to restart their livelihood after the community quarantine. Many of the members or 35% would still need relief goods, especially food, immediately after the quarantine and A few or 12% need work to have source of income.

The rapid community assessment showed that 77% of respondents request for cash assistance to restart their livelihood after the community quarantine. Many of the members or 35% would still need relief goods, especially food, immediately after the quarantine and A few or 12% need work to have source of income.