Category: Social Entrepreneurship

-

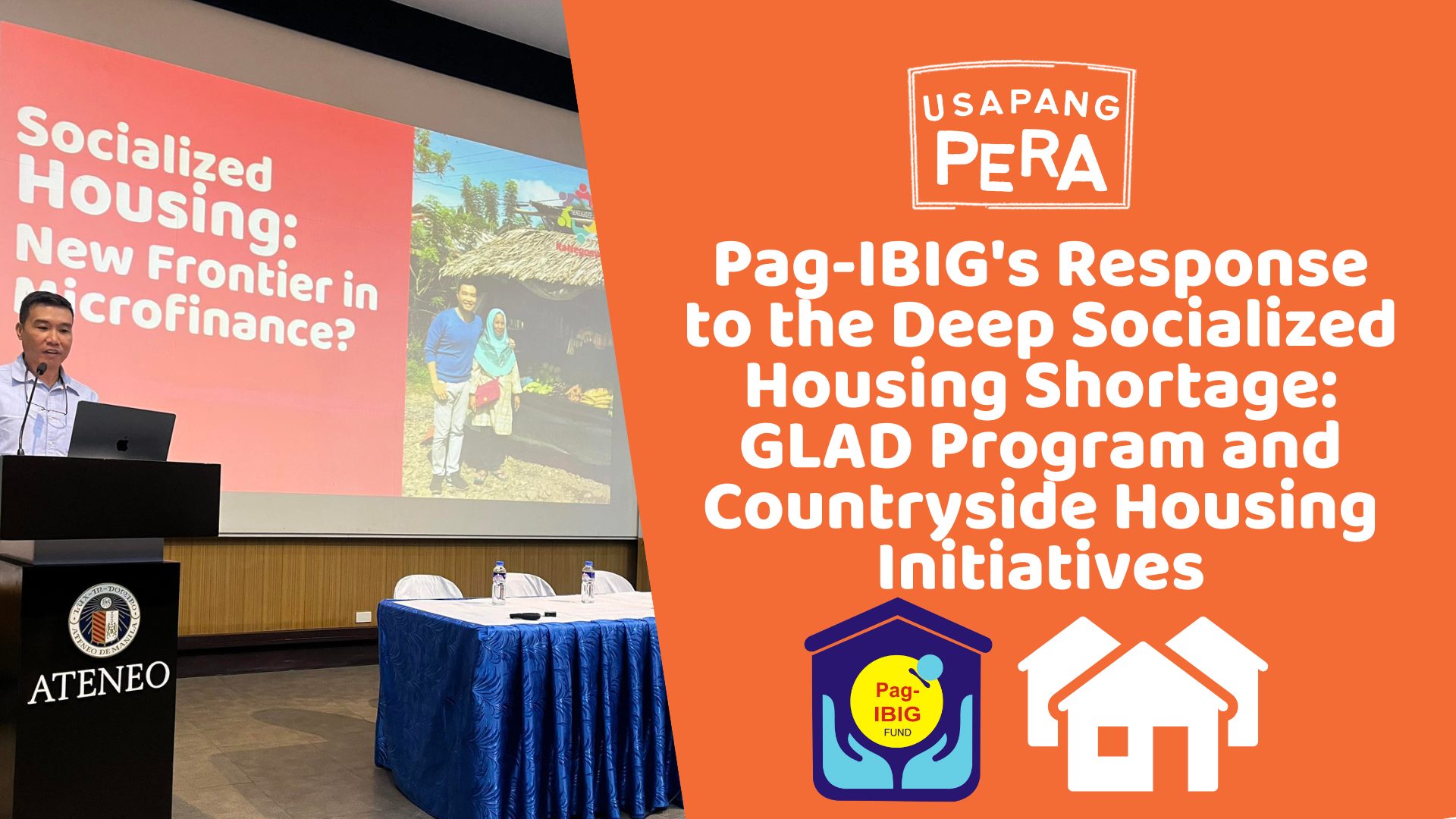

Pag-IBIG’s Response to the Deep Socialized Housing Shortage: GLAD Program and Countryside Housing Initiatives

At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit held at the Ateneo de Manila University, Pag-IBIG’s Chief Executive Officer, Marilene Acosta, highlighted the drastic drop in socialized housing production for 2023 and outlined the institution’s strategic initiatives to address this pressing concern. Acosta reported a distressing figure, revealing that in 2023, the production of socialized housing units…

-

Gawad Kalinga Ateneo Unveils Success in Building Communities at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, Ms. Norlie Corneby of Gawad Kalinga Ateneo shared a profound narrative of community transformation and resilience, illustrating the organization’s triumphs in socialized housing. Held on March 18-19, 2024, at the Ateneo de Manila University, the summit, organized by the Ateneo Center for Social Entrepreneurship (ACSent) and Social Enterprise Development…

-

OSHDP Advocates for Robust Partnerships and Data-Driven Strategies in Socialized Housing

At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, held at the Ateneo de Manila University on March 18-19, 2024, Engr. Marcelino Mendoza of the Organization of Socialized and Economic Housing Developers of the Philippines Inc. (OSHDP) provided an in-depth look at the vital role mass housing developers play in addressing the country’s urgent housing needs. Organized by…

-

Citihub Founder Panya Boonsirithum Advocates for Affordable Urban Housing at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

In a striking presentation at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, held on March 18-19, 2024, at the Ateneo de Manila University, Panya Boonsirithum, the founder of Citihub, shared his visionary approach to addressing Metro Manila’s housing crisis. Organized by the Ateneo Center for Social Entrepreneurship (ACSent) and Social Enterprise Development Partnerships Inc. (SEDPI), the summit…

-

Socialized Housing Production Hits Record Low,SHDA Highlights Compliance Challenges at Housing Summit

During the enlightening 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, Santiago F. Ducay from the Subdivision and Housing Developers Association (SHDA) presented a concerning update on the state of socialized housing in the Philippines. The year 2023 saw the production of socialized housing units plummet to a historic low since 2001, with only 10,113 units completed. This stark…

-

DENR’s Engr. Romeo P. Verzosa Outlines Land Titling Reform at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

The second day of the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit, co-organized by the Ateneo Center for Social Entrepreneurship (ACSent) and Social Enterprise Development Partnerships Inc. (SEDPI) on March 18-19, 2024, at Ateneo de Manila University, featured Engr. Romeo P. Verzosa, Assistant Director of the DENR – Land Management Bureau. His presentation provided an essential overview of…

-

SHFC Aims to Transform Lives with Resilient Communities Amid Housing Challenges

At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit held at Ateneo de Manila University, Atty. Junefe G. Payot from the Social Housing Finance Corporation (SHFC) presented an approach to combat the Philippines’ housing backlog through resilient community-driven projects. Amidst a critical period where the production of socialized housing units plummeted to an all-time low in 2023, SHFC’s…

-

Senator Risa Hontiveros Advocates for Innovative Social Housing Solutions at the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit

Manila, Philippines – At the 2nd Socialized Housing Summit held at Ateneo de Manila University, Senator Risa Hontiveros delivered a compelling speech, outlining the dire need for innovative and inclusive solutions to the Philippines’ housing crisis. Addressing a gathering of developers, microfinance institutions, academes and housing advocates, Senator Hontiveros emphasized the dream of every Filipino…

-

Empowering the Marginalized: SEDPI’s Innovative Path in Nanoenterprise Development

Empowering the Marginalized: SEDPI’s Innovative Path in Nanoenterprise DevelopmentVince RapisuraJanuary 11, 2024 Established in 2004, the SEDPI Group of Social Enterprises focuses on empowering marginalized Filipino communities via sustainable nanoenterprise growth. Their multifaceted approach includes nanofinancing, social investments, and financial education, addressing poverty and promoting financial stability. Despite advances in microfinance, poverty and high indebtedness…

-

SEDPI KaNegosyo: Revolutionizing Microfinance in Mindanao

Bayugan City, Agusan del Sur – SEDPI KaNegosyo, a pioneer in microfinance, continues to set itself apart from conventional microfinance institutions with its innovative approach to financial services, particularly in the thriving communities of Mindanao. Since its inception, SEDPI KaNegosyo has been on an impressive trajectory of growth. From a modest beginning with two branches…